May 29, 2019 Harnessing the Power of Play to Teach

We are never more fully alive, more completely ourselves, or more deeply engrossed in anything, than when we are at play.

—Charles E. Schaefer, pioneer in the field of play therapy

Following excerpt from the Inspired Educator, Inspired Learner book by Jen Stanchfield:

Never underestimate the power of play in learning! Play is a serious subject. There is a great deal of literature and research on play, and varied definitions of what constitutes true play, types of play, and stages of play.

Never underestimate the power of play in learning! Play is a serious subject. There is a great deal of literature and research on play, and varied definitions of what constitutes true play, types of play, and stages of play.

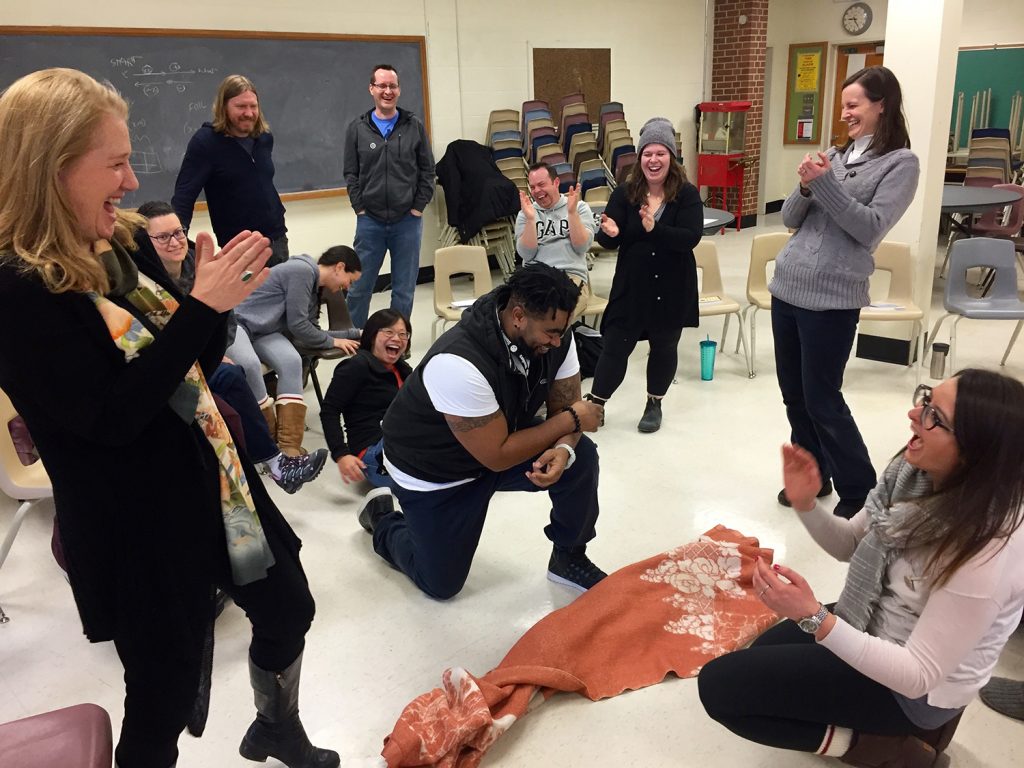

My working definition of playful learning involves engaging learners in educational activities, games, and creative academic group-building projects that promote learning. Playful learning experiences are:

• attractive, enjoyable, and rewarding, including moments of challenge and frustration balanced with support, success, and joy of achievement;

• engaging and active, including movement, social interaction, and use of multiple senses;

• intrinsically motivating—inspiring control and ownership on the part of learners;

• focused on the process (and lessons learned along the way) or a means to an end versus the product or outcome of the game; and

• flexible and changing.

Playful learning situations enhance academic and social-emotional outcomes, create collaborative and supportive learning communities, instill a desire to learn, and inspire a sense of discovery. Learners of all ages can develop and practice necessary life skills through play. Well respected

proponents of 21st century learning and innovative teaching promote playfulness, games, and collaborative group challenges in teaching (Wagner, 2012; Trilling & Fadel, 2009). Play and active playful communication and problem-solving challenges are vehicles educators

can use to meet the diverse needs of learners, they are tools to teach, review, and reinforce academic content in novel and engaging ways.

We learn some of our most basic life skills through play. Play contributes to the development of one of our most important brain functions—the ability to control and modify our behavior in order to reach a goal. Adults, adolescents, and children all learn and can potentially “change their brains” through play (Aamodt &Wang, 2011). Research from educational neuroscience suggests that interactive social play improves executive function. “Executive function” is the term used by neuroscientists to describe cognitive processes that regulate, manage, and control other cognitive functions. These include attention, problem solving, working memory, reasoning, inhibition, evaluating, and controlling one’s actions. These skills promote success in school, personal life, and work. They are emphasized in social-emotional learning and 21st century skills development programs. Poor executive function is associated with high dropout rates, drug use, and crime. Good executive function is a better predictor of success in school and later in professional life than a child’s IQ (Diamond, 2010).

Developing and Reinforcing Positive Behaviors

People learn self-regulation when they practice taking turns and focusing on the different tasks necessary to participate in a game. Playing safely, staying within boundaries, following rules, and other regulatory skills are necessary for, and practiced through, play. Structured and unstructured interactive play is a powerful way to improve executive function in children and adults because many of the cognitive processes involved have plasticity and can be developed through practice. Use of these skills or mental capacities builds that ability. Playful learning in a safe supportive environment promotes inclusion and inherently involves opportunities for adaptation and creativity. A playful approach facilitates learning by arousing attention and increasing sensory gain (Aamodt & Wang, 2011; Willis, 2010a).

Harnessing the Power of Play to Teach

Because play is desirable, participants are motivated to practice rules of self-regulation in ways they might not in everyday life. Games require social rules, boundaries, and structure in order to work. Lev Vygotsky, a twentieth-century Russian psychologist and proponent of experiential learning methods and the power of play to teach, argued that, in play, a child learns to follow social rules because following social rules leads to pleasure. He stated, “by subordinating themselves to rules, children renounce what they want, since subjection to rule and renunciation of spontaneous impulsive action constitute the path to maximum pleasure in play” (1933, Translation Voprosy Psikhologii, 1966).

Many of the cognitive processes involved in executive function have plasticity and can be developed through practice. Play, especially play that involves problem-solving tasks, social interaction, planning, reasoning, and multiple senses, encourages mental growth and self-regulation skills (Aamodt & Wang, 2011; Bodrova & Leong, 2007; Diamond, 2010). Studies on brain structure and chemistry show that play activates norepinephrine (also known as noradrenaline), which arouses attention, increases sensory gain and the impact sensory information makes on the brain. It also can improve brain plasticity in some neurons (Aamodt & Wang, 2011; Willis 2010b). The conditions of play generate the signals and processes in the brain that enhance learning by arousing attention.

Play and Dopamine

Dopamine an important neurotransmitter involved with awareness, attention, and mood, is increased when we experience something pleasurable. Dopamine levels are associated with the reward center of the brain and the heightened sense of pleasure that characterizes rewarding experiences. Playful learning experiences can trigger this “reward center” in the brain increasing positive associations with learning. Engaging participants in learning activities that correlate with increased dopamine release will likely get them to respond not only with pleasure, but also with increased focus, memory, and motivation (Willis, 2010b, 2012). Playful approaches that use multiple senses can create multiple pathways to learning by engaging students socially, emotionally, physically, and intellectually. Educational neuroscientists emphasize that the more ways in which something is learned and practiced, the easier it is to recall and access that information (Medina, 2014; Willis, 2014).

Many are concerned that play gets in the way of time spent on academics. I would argue that play doesn’t have to be separate from academic or training content. Integrating play leads to more effective teaching and learning. Studies on play and learning show that children in classrooms where teachers used play as a teaching tool for sustained periods of time scored higher in literacy skills (Bodrova & Leong, 2007). Play helps educators connect with their students and learn ways to support them. Games and activities help differentiate instruction and provide opportunities for formative assessment. When using interactive activities for review, formative assessment doubles as a learning and teaching tool, an idea Tomlinson (2013) promotes in her work on differentiation (see page 21).

Play inherently involves opportunities for inclusion, adaptation, and creativity. Playful activities can promote inclusivity bringing learners of various abilities together in the classroom. When I go into my local middle school to offer community building and active academic review, we make sure all students in that grade are present, even if they are usually pulled out for special education support during that period. This initiates positive changes in the students’ social interactions with each other. Students who are often excluded have opportunities for positive social interactions with their peers. Students who are traditionally known as high academic achievers and may hold preconceived notions about “special education” students gain new perspectives on the many skills and insights their peers bring to class. I also see teachers gain new perspective in this way. Frequently it is the student who has in the past struggled academically or behaviorally who offers the creative practical solution to a problem or the profound reflective insight that pulls the lesson together.

Play inherently involves opportunities for inclusion, adaptation, and creativity. Playful activities can promote inclusivity bringing learners of various abilities together in the classroom. When I go into my local middle school to offer community building and active academic review, we make sure all students in that grade are present, even if they are usually pulled out for special education support during that period. This initiates positive changes in the students’ social interactions with each other. Students who are often excluded have opportunities for positive social interactions with their peers. Students who are traditionally known as high academic achievers and may hold preconceived notions about “special education” students gain new perspectives on the many skills and insights their peers bring to class. I also see teachers gain new perspective in this way. Frequently it is the student who has in the past struggled academically or behaviorally who offers the creative practical solution to a problem or the profound reflective insight that pulls the lesson together.

The Inspired Educator, Inspired Learner book explores creative, cooperative, challenging play. Healthy competition that emphasizes the process over the outcome is involved in many of the activities and score-keeping is de-emphasized. Play is combined with reflective practice to create lasting lessons and carry learning forward.

Why Play is Such a Valuable Tool

• Brains need breaks from focused attention like that experienced in a lecture or direct instruction (Medina, 2014). Play with a purpose can be a vehicle for giving learners “brain breaks” while still making the most of classroom time.

• Play promotes and supports positive behaviors (Diamond, 2010) and develops communication skills. Socialization is practiced and reinforced through the problem-solving, rule-making, negotiation, and planning inherent in games.

• Play helps people develop executive functions such as self-regulation and impulse control (Diamond). Focusing on the different tasks needed to successfully play a game (i.e., take turns, follow rules, play safely, stay within boundaries) promotes these skills.

• Play brings joy to learning. Research shows that pleasurable associations with learning reduce stress, increase attention and retention, and encourage future learning (Willis, 2010b, 2014).

• Play involves movement and uses multiple senses. Movement is associated with increased attention and retention (Medina). Multiple ways of practicing and reinforcing information increase neuronal pathways leading to stronger memories and recall ability (Willis).

• Play promotes inclusion. Playful, interactive activities promote social and communication skills; they are effective tools for bringing all learners of various abilities together.

• Play symbolizes the real world. Engaging in play involves modeling and practicing common, real life social interactions and situations (i.e., creativity, adaptation, exploration of abstract themes). Creative play helps learners understand where their interests and strengths lie.

• Play develops creativity and innovation. Interactive games require problem-solving and adaptation to changing space, materials, and players—mistakes and failure are part of the process. This is a premise of experiential learning, 21st century skills, and social-emotional learning.

• Play is motivating and creates conditions for active engagement. Play in an academic setting involves group members who might not engage in more formal lecture situations. (Time and time again, I see reluctant participants unable to resist play situations and non hand-raisers actively participate in academic discussion when it comes in the guise of a game.)

• Play helps develop theory of mind—the understanding that others think differently than we do (Aamodt & Wang, 2011). Watching others at play promotes empathy and understanding different views and perspectives. Through observing learners in play situations, teachers gain valuable insights into their individual needs and personalities.

References:

Aamodt, S., & Wang, S. (2011). Welcome to Your Child’s Brain: How the Mind Grows from Conception to College. New York: Bloomsbury.

Bodrova, E., & Leong, D. J. (2007). Tools of the mind (Second ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Medina, John. (2014). Brain Rules: 12 Principles for Surviving and Thriving at Work, Home and School. Second Edition Seattle, WA: Pear Press.

Sousa, D. A. (2010). Mind, Brain, and Education: Neuroscience Implications for the Classroom. Bloomington,IN: Solution Tree Press.

Vygotsky, L. (1933). Play and its role in the mental development of the child. Psychology and MarxismInternet Archive: Lev Vygotsky Archive, Voprosy psikhologii, 1966, No. 6; (Translated by Catherine Mulholland). Retrieved November 15, 2012, from http://www.marxists.org/archive/vygotsky/works/1933/play.htm.

Willis, Judy. (2008). How Your Child Learns Best. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks.

Willis, J. (2013). Unlocking student-directed learning and concept acquisition. Lecture conducted at The

Learning & the Brain Conference: Engaging 21st Century Minds. Boston, MA.

Sousa, D., & Tomlinson, C. A. (2010). Differentiation and Brain: How Neuroscience Supports the Learner- Friendly Classroom. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press Online Resources.

Stanchfield, Jennifer (2014). Inspired Educator, Inspired Learner: Experiential, Brain-Based Activities and Strategies to Engage, Motivate, Build Community and Create Lasting Lessons. Bethany, Ok: Wood N Barnes Publishing

Tomlinson, C. A. (2013, April). “The Brain and Differentiation.” Keynote Luncheon Presentation. New England League of Middle Schools Conference. Providence, RI.

No Comments